Newsletter June 2015: Market Observations

June 4, 2015

The overriding theme of the auctions in New York last month was records: the record for the most expensive painting ever sold at auction, the record for the first ever billion dollar week of sales for one auction house, a record number of sales crammed into one week, a record number of lots on offer, a record number of catalogues jamming the postbox in the preceding weeks, a record number of collectors, dealers and spectators suffering from auction fatigue…. it was undoubtedly an extraordinary week, but one that has left commentators wondering the perpetual question… what happens next?

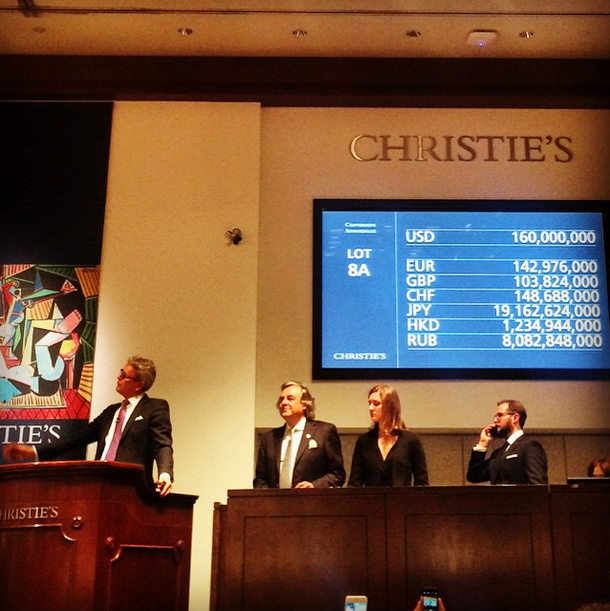

Will it be a moment that we look back on in years to come and wonder what on earth was going on, or will it have been just another watershed moment in the seemingly relentless boom at the top of the art market? The mega-sale at Christie’s, where the Picasso broke the record at $179 million, and the sale totalled $1.4 billion, was a surprisingly dull auction to watch. The action was concentrated on five or six telephones with virtually no participation from those seated in the room. As more than half the lots were guaranteed (effectively pre-sold) it was predictable and lacked fireworks. Perhaps more importantly, it was extremely difficult to gauge whether this is an accurate barometer of the state of the market. On one hand, the many millions of dollars that changed hands that evening indicates a market which continues to go from strength to strength. But on the other hand, this may have been an impressive, stage-managed and well-publicised production which, in reality, had fewer protagonists than one might imagine. If this is the case, it’s possible that the top of the market is less robust than we are lead to, or want to believe.

Of course this is pure speculation. It comes as no surprise that great and rare masterpieces make tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. What is harder to comprehend is the vast prices achieved for living, and in some cases, relatively young artists. Take Christopher Wool (b. 1955) for example. Wool is undoubtedly an artist of immense talent and innovation, but when a 1991 work, “Untitled (Riot)” makes just short of $30 million, a price for which one could acquire exceptional works by artists such as Rembrandt, Monet, Raphael and Rodin, one does begin to wonder if the market has detached from reality altogether. This particular sector of the contemporary market is trend-driven and volatile; artists whose stock once took a generation to rise or fall may now only have a shelf life of five years. This is not the case for Christopher Wool, an artist of established critical acclaim, but the question remains: what will his work be worth in 10, 20 or 30 years? Will it continue to grow exponentially, or one day be worth a fraction of its value today?

We can’t answer this, but instead heed the words of Warren Buffet, who famously said ‘it’s only when the tide goes out that you learn who’s been swimming naked’.