Radical Geometry, Royal Academy, review: ‘stunning’

July 4, 2014

The Radical Geometry exhibition of abstract South American work utterly transforms our understanding of 20th-century art, says ALASTAIR SMART

I lose track of the number of exhibitions that have promised a “radical reappraisal” of an artist or movement – only to be as revelatory as a soggy sock. The RA bucks that trend utterly, however, with its new show of abstract South American art from the Thirties to the Seventies.

As we all know, Abstraction had developed in Europe – via Impressionism and later movements – in the early 20th-century, but where Radical Geometry comes into its own is in revealing how vital artists from Montevideo to Caracas were in taking things forward. They adapted the new visual language of abstraction – specifically, geometric abstraction – to express the progress and prosperity emanating from South American countries at the time.

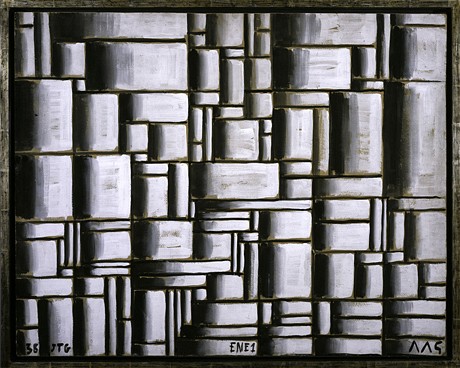

In the wake of the Great Depression, Spanish Civil War and Second World War, exiles and refugees aplenty made their way to the Americas to start anew. With them came knowledge of the European precedents of geometric abstraction (Bauhaus, Russian Constructivism, Mondrian) and our tale begins with Joaquín Torres-García, who returned to his native Uruguay in 1934 after decades in Paris.

His grids are filled with pictographic elements that recall the relief stonework on pre-Columbian temples: suns, anchors and fish in Constructive Composition 16’s case. He united the ancient and avant-garde, in a bid to root a new artistic utopia firmly in South America.

Across the River Plate, in Buenos Aires, artists were more explicitly political, advocating geometric abstraction as the art form of coming social revolution – given its universal language and anti-individualist aesthetic. As had been the case in the early years of the Soviet Union, abstract art and communism dovetailed.

Among the standout works are Juan Melé’s Irregular Frames No. 2 (1946), a geometric composition of jagged shape that overthrew the tradition of paintings with rectangular frames, which since the Renaissance had illusionistically suggested a window onto the world.

Time and again, we see a turning away from Europe. Indeed, in some way, surely the very embrace of abstraction was a rejection of the strict figurative tradition that the Conquistadores had promulgated in churches across the New World.

By the Fifties, our focus turns to newly democratic, fast-industrialising Brazil. National confidence was expressed in its new, International Style capital, Brasilia. In Rio de Janeiro, meanwhile, the Neoconcrete artists were making geometric abstraction more participatory: through sculpture.

Lygia Clark’s Bichos are hinged, creature-like works of aluminium, with geometric planes that you can bend into various arrangements. With his parangolés, in turn, Helio Oiticica went so far as to envisage geometric compositions as clothing: to be worn during dances, shattering the stuffy notion that art must appear on walls or on pedestals.

Understandably, the parangoles appear here only as objects: the RA hasn’t employed a group of dancers. And this reflects the unshowy effect of Radical Geometry as a whole: it acts as a sage corrective to the stereotype of South America as a place of tropical colour and excess sensuality. The palettes are muted. What’s more, there’s none of the freestyle brushwork we associate with the contemporaneous Abstract Expressionists in New York.

One can’t help but compare the artists with their US and European counterparts throughout, and one sees a stunning alternative history of 20th century art playing out before our eyes. (Credit to Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, upon whose vast collection the works are drawn and whose mission it has become to open our eyes to South American excellence.)

The show’s latest works, from oil-rich Venezuela, invite comparison to Op Art. In his series of painted Physichromie structures, Carlos Cruz-Diez deploys vertical strips which change colour according to the viewer’s position and the ambient light. Jesús Rafael Soto shared his fascination with light’s transitory effects, but was interested most in pioneering an art that was kinetic. His Penetrables are walk-through cubes with shimmeringly lit strands of plastic hanging from ceiling to floor.

Sadly there isn’t room to include an example in the compact Sackler Galleries – perhaps one of only two regrets I have about this exhibition. The other is the narrative of unremitting positivity. Latin America was no stranger to dictatorships in the 20th century, and I’d have liked to hear more about how certain artists, at certain times, actually used abstraction as a means of subsuming their political dissent.

That said, one shouldn’t quibble. This is a quietly marvellous show. And to all those who once suffered excruciatingly through maths classes, trust me: geometry has never been so riveting.

Original Article: The Telegraph